The Constitutional and Legal Framework: Laws That Control Federal Spending

Federal budget execution isn't just bureaucratic process—it's constitutional law in action.

Before understanding how federal budget execution works, you need to understand the Constitutional "power of the purse" and the laws that implement it.

Federal budget execution isn't just bureaucratic process—it's constitutional law in action.

The Constitution's Appropriations Clause and four laws control every dollar the federal government spends: the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, the Purpose Statute, the Antideficiency Act, and the Impoundment Control Act of 1974. Together, the Appropriations Clause and these laws create the fiscal framework we discussed in our earlier posts.

Understanding these laws explains why OMB approval is required before agencies can spend, why September spending surges happen every year, and why impoundments are illegal but still happen.

Quick Reference: The Constitution and Four Laws You Need to Know

When tracking federal budget execution, the Constitutional "power of the purse" and four laws control every dollar:

Appropriations Clause (Article I, Section 9)

- What it does: Requires congressional approval for all spending

- Key question: Did Congress appropriate funds for this program?

The Four Implementing Laws:

1. Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 (31 U.S.C. § 1513)

- What it does: Gives OMB authority to apportion (release) funds in increments

- Key question: Has OMB apportioned the funds Congress appropriated?

2. The Purpose Statute (31 U.S.C. § 1301(a))

- What it does: Prohibits agencies from spending funds on unrelated items

- Key question: Can the agency legally obligate funds for a specific purpose?

3. Antideficiency Act (31 U.S.C. § 1341-1342)

- What it does: Prohibits agencies from spending more than OMB apportions

- Key question: Can the agency legally obligate funds without violating the ADA?

4. Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (2 U.S.C. §§ 681-688)

- What it does: Requires OMB to release appropriated funds (with limited exceptions)

- Key question: Is OMB illegally withholding funds Congress appropriated?

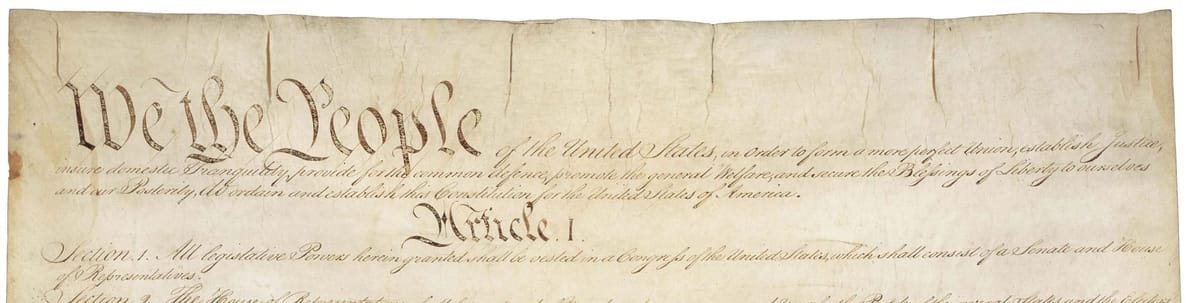

Article I, Section 9: The Constitutional Foundation

The Appropriations Clause is nine words long:

"No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law."[^1]

This single sentence establishes the core principle: Congress controls the purse. The executive branch cannot spend money without congressional authorization, no matter how urgent the need or how strongly the President believes in the policy.

The Founders deliberately gave spending power to the legislative branch—the branch closest to the people—as a check on executive authority. Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist No. 58 that "the power over the purse may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon... for obtaining a redress of every grievance."[^2]

What this means in practice: Every dollar in the federal budget must be authorized by an appropriations law passed by Congress and signed by the President. Executive agencies cannot create their own spending authority, redirect appropriated funds to unauthorized purposes, or continue spending after an appropriation expires.

The Appropriations Clause is why we track appropriations bills—they're the Constitutional authority for everything that follows.

- What is an Appropriation? Understanding Congress's Power of the Purse

- How Appropriations Work: Duration and Distribution

The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921: Creating OMB's Apportionment Authority

For the first 130 years of the Republic, agencies could spend appropriated funds as soon as Congress provided them. This changed with the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921.[^3]

The 1921 Act created the Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget) and gave it authority to apportion appropriations—distributing funds to agencies in increments rather than all at once. The original purpose was straightforward: prevent agencies from spending their entire annual appropriation in the first few months and running out of money before the fiscal year ended.[^4]

Section 1513 of Title 31 (derived from the 1921 Act) gives OMB broad discretion:

"An appropriation or fund may be apportioned on a basis other than a monthly basis, if the head of the agency... determines and reports immediately to the President and Congress that the apportionment is necessary to carry out the purpose of the appropriation."[^5]

What this means in practice: OMB apportions funds in whatever increments it deems appropriate—quarterly, monthly, by project, or according to agency performance. Agencies must submit an SF-132 apportionment request and receive OMB approval before they can obligate funds, even though Congress has already appropriated them.

This is why we track apportionments—they control when appropriated funds actually become available to agencies.

The apportionment process gives OMB significant leverage over agency operations. An agency with a $1 billion annual appropriation might only have $250 million available each quarter. If OMB delays apportionment, the agency can't spend—even if the work is urgent and Congress provided funding.

The Purpose Statute: You Can't Buy Tanks with Library Money

The Purpose Statute is the simplest of the four laws—31 U.S.C. § 1301(a) states:

"Appropriations shall be applied only to the objects for which the appropriations were made except as otherwise provided by law."[^24]

In plain English: Congress appropriates funds for specific purposes, and agencies must spend the money on those purposes—not something else.

If Congress appropriates $10 million "for the purchase of books and periodicals" the agency can't use that money to buy office furniture, pay salaries, or fund travel—even if the agency desperately wants or needs those things. And you definitely can't use the hypothetical appropriation to buy tanks or planes or roads or use it on space exploration. The appropriation is limited to its stated purpose.

What this means in practice: The Purpose Statute creates three types of violations that GAO routinely investigates:

- Wrong program: Using funds appropriated for Program A to pay expenses for Program B

- Wrong purpose: Using "operations and maintenance" funds for capital construction projects

- Augmentation: Using one appropriation to supplement another appropriation that has insufficient funds[^25]

How agencies violate it accidentally: Unlike the Antideficiency Act (which agencies track regularly), the Purpose Statute depends on correctly categorizing expenses. An obligation that's legitimate under one appropriation might be illegal under another. Agencies need strong financial management systems and clear policies about what each appropriation can fund.

The classic example is an agency that runs out of travel money in August and tries to pay for travel using its training appropriation. Even if the travel is for training purposes, this violates the Purpose Statute—Congress appropriated separate pots of money for travel and training, and the agency can't commingle them without statutory authority.

How it connects to the other laws: The Purpose Statute works with the Appropriations Clause to limit executive discretion. The Clause says "you need congressional approval to spend." The Purpose Statute says "you must spend the money the way Congress specified." Together, they prevent the executive branch from redirecting appropriated funds to unauthorized purposes—even if those purposes seem reasonable.

The Antideficiency Act: Budget Jail?

The Antideficiency Act (ADA) is one of the most important—and least understood—laws in federal budget execution. It prohibits agencies from:

- Obligating or spending more money than Congress appropriated[^6]

- Obligating funds before they're apportioned by OMB[^7]

- Accepting voluntary services (which could obligate the government to pay later)[^8]

Violating the ADA is a federal crime. An employee who knowingly violates the Act can be fined up to $5,000, imprisoned for up to two years, and removed from federal service.[^9]

What this means in practice: Even if Congress appropriated $1 billion, an agency can only obligate the amount OMB has apportioned. If OMB apportions $250 million and the agency obligates $300 million, that's an ADA violation—a federal crime.

The Act also explains why agencies are obsessed with "unobligated balances" of expiring funds. Money that's appropriated but not yet obligated represents spending authority the agency has but hasn't used. At the end of the fiscal year, agencies face "use-it-or-lose-it" pressure: obligation authority expires, and unobligated balances may be rescinded by Congress.

The Antideficiency Act creates the September spending surge. Agencies rush to obligate remaining funds before the fiscal year ends on September 30, leading to predictable patterns in SF-133 execution data.[^10]

It also is the legal mechanism that underpins a government "shutdown" or a lapse in appropriations. Without an enacted appropriation at the beginning of the fiscal year or at the expiration of a continuing resolution, any spending would run afoul of the ADA.

The ADA and apportionment together: These two laws create a sequential approval process:

- Congress appropriates (creates legal authority to spend)

- OMB apportions (releases funds in increments)

- Agencies obligate (commit funds through contracts, grants, etc.)

An agency can't skip step 2-apportionments have the force of law. This is why tracking execution requires both apportionments (what OMB released) and SF-133 data (what agencies obligated).

- How to Read a Continuing Resolution

- What is a Government Shutdown?

The Impoundment Control Act of 1974: Limiting Presidential Withholding

The Impoundment Control Act (ICA) is the most politically contentious of the four laws. It restricts the President's authority to withhold or delay spending that Congress has appropriated.[1]

The constitutional tension is straightforward: Appropriations are laws that Congress passes—and the President signs—that authorize spending from the Treasury. Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution provides that the President:

...shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed...

If appropriations are laws, does the Take Care Clause require the President to spend the money? Or does "faithfully executing" the laws include discretion to withhold spending when circumstances change?

President Nixon answered that question by impounding billions in highway, housing, and environmental funds, arguing the executive had inherent authority to decline spending on policy grounds.[2] His administration claimed the Take Care Clause granted discretion, not just a duty to spend.

Congress disagreed. In 1974, Congress passed and President Nixon signed the ICA: the President must spend appropriated funds unless Congress agrees to rescind them or specific legal exceptions apply.

The ICA created two categories of impoundment:

1. Rescissions (permanent withholding): If the President wants appropriated funds to be permanently cancelled, the President must send a rescission proposal to Congress asking Congress to rescind the funds in the proposal. If Congress doesn't pass a law approving the rescission within 45 days, the funds must be released.[3] While rescission proposals under the ICA are rare, the act of rescinding funds is not rare. Each year Congress rescinds funding through the regular appropriations process. To put it simply-in this section of the ICA, the Congress gave the Executive branch a formalized way to ask it to rescind funds.

2. Deferrals (temporary delay): If the President wants to temporarily delay spending, he must notify Congress with a "special message" explaining the deferral. Congress can override the deferral by passing a resolution.[4]

The ICA also requires the President to report any action that "delays or precludes the obligation or expenditure of budget authority."[5] This includes apportionment actions that withhold funds.

What this means in practice: Under the ICA, OMB cannot simply refuse to apportion congressionally appropriated funds. A refusal to apportion is an impoundment, which requires formal notification to Congress and justification under one of the limited exceptions (prudent cash management, emergencies, etc.).

But here's the catch: the ICA is difficult to enforce.

The Congress and Government Accountability Office (GAO) can investigate alleged impoundments, but neither have the immediate ability to force the Executive branch to spend the money. If OMB withholds apportionments and doesn't report it as an impoundment, the GAO will issue a report. But the only real remedy to get the Executive branch to obligate funds is litigation—which takes months or years.[6]

This is why tracking apportionments and obligational reporting matters. A pattern of delayed apportionments and low or slow spending can reveal unreported impoundments.

How These Laws Work Together: A Real Example

Let's walk through a real example using HHS's Head Start program—and a case where the Impoundment Control Act was actually violated.

Congress appropriated $14.789 billion for the Children and Families Services Programs account (TAFS 075-1536) in the FY2025 appropriations bill.[7] This account funds multiple programs, including Head Start formula grants, child welfare programs, and community services. The largest component is Head Start Category A (formula grants to existing grantees): $12.178 billion, which provides educational, nutritional, health, and social services to low-income children through approximately 1,600 grant recipients across all 50 states.

Step 1: Appropriations Clause

The appropriation creates legal authority for HHS to spend up to $14.789 billion across all programs in this account. Without this appropriation, HHS has no authority to obligate funds for these purposes.

The Head Start Act specifies exactly how HHS must distribute the money: by formula to existing Head Start grant recipients.[8] HHS can't arbitrarily withhold funds or redirect them to other programs—Congress controls that.

Step 2: Budget and Accounting Act (Apportionment)

HHS submits an SF-132 apportionment request to OMB. Under normal circumstances, OMB would apportion the funds on a schedule that allows HHS to disburse grants throughout the fiscal year, consistent with Head Start agencies' operational needs.

This is where we can see the problem developing. Here's what OMB actually apportioned for Head Start Category A (formula grants) in FY2025:

| Quarter | Amount Apportioned |

|---|---|

| Q1 (Oct-Dec 2024) | $4.30 billion |

| Q2 (Jan-Mar 2025) | $1.18 billion |

| Q3 (Apr-Jun 2025) | $4.78 billion |

| Q4 (Jul-Sep 2025) | $1.91 billion |

| Total | $12.18 billion |

Look at Q2: only $1.18 billion apportioned for the entire quarter. This is the bottleneck.

Step 3: SF-133 Shows the Execution Problem

SF-133 reports track actual obligations—when HHS commits funds through grants to Head Start agencies. Line 2001 shows "direct obligations incurred" against the Category A (by quarter) apportionment.

Here's what the execution data reveals:

| Month | FY2025 Obligations | Monthly Velocity | FY2024 Obligations | Monthly Velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov | $1.03 billion | — | $0.95 billion | — |

| Dec | $1.79 billion | $0.77 billion | $1.58 billion | $0.63 billion |

| Jan | $2.27 billion | $0.48 billion | $2.14 billion | $0.56 billion |

| Feb | $2.70 billion | $0.43 billion | $2.58 billion | $0.43 billion |

| Mar | $3.16 billion | $0.46 billion | $3.69 billion | $1.12 billion |

| Apr | $4.43 billion | $1.26 billion | $5.24 billion | $1.54 billion |

| May | $6.52 billion | $2.09 billion | $6.37 billion | $1.13 billion |

| Jun | $9.69 billion | $3.17 billion | $8.46 billion | $2.09 billion |

The smoking gun: By end of March, FY2025 obligations ($3.16B) lagged $530M behind FY2024 ($3.69B). Then in Q3, after OMB finally released funding, there's a $3.17B velocity spike in June—the catch-up.

Step 4: The Apportionment Footnote

But why did OMB delay the Q3 apportionment? The answer is buried in Footnote A2 attached to Line 6003 (the Q3 apportionment of $4.78 billion):

"Amounts apportioned, but not yet obligated as of the date of this reapportionment, with the exception of funds which were expected to be obligated on financial assistance to designated Head Start agencies on or around April 1, 2025, are available for obligation consistent with the latest agreed-upon spending plan for Fiscal Year 2025 between the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)... In the absence of an agreed-upon spend plan between HHS and OMB, HHS may obligate funds on this line only as necessary for Federal salary and payroll expenses or making payments otherwise required by law, but such funds may not be used for competitive paneling activities or to make any new Head Start agency designations."

Translation: OMB froze $4.78 billion unless HHS submitted a spending plan that OMB approved. Without OMB's agreement, HHS could only pay federal employee salaries—not make grants to Head Start agencies serving 20,000 children.

Step 5: Antideficiency Act

Even though Congress had appropriated $14.789 billion for the full account (including $12.178 billion for Head Start formula grants), and even though the Head Start Act mandates distribution by formula, HHS was legally blocked from spending because OMB had apportioned the funds with restrictive conditions.

Step 6: Impoundment Control Act

Here's where the violation occurred.

The Impoundment Control Act requires the President to report any action that "delays or precludes the obligation or expenditure of budget authority." Footnote A2's spending plan requirement is exactly that kind of delay—OMB withheld apportionments and imposed conditions beyond what the law requires.

HHS never sent a special message to Congress explaining the withholding, as required by the ICA. Head Start agencies across 23 states reported they couldn't access federal funds. Programs serving nearly 20,000 children faced delays.[9]

In July 2025, GAO issued a decision: HHS violated the Impoundment Control Act.[10]

Why was this illegal? The Head Start Act is a formula grant program—the law mandates that HHS distribute funds according to the statutory formula. Under the ICA's "fourth disclaimer," the President cannot defer funds for programs where the law requires spending.[11] OMB had no legal authority to impose the spending plan requirement in Footnote A2.

The enforcement gap in action: By the time GAO issued its decision (July 2025), the withholding had lasted from January through early April 2025. Some Head Start agencies had already laid off staff or reduced services. The ICA violation was clear, but enforcement was slow.

What the three data points reveal together:

- SF-133 (execution data): Shows obligations lagging $530M behind prior year by March

- Apportionment schedule: Shows OMB only released $1.18B in Q2 (the bottleneck)

- Apportionment footnote: Reveals OMB's condition—spending plan approval required

Without tracking all three sources, you can't see the full picture. The SF-133 data shows the symptom (delayed spending). The apportionment schedule shows the mechanism (restricted release). The footnote reveals the illegal condition (spending plan veto).

Why This Matters for Budget Tracking

These four laws explain the structure of federal budget execution:

- Appropriations (Congress controls): Tracked via appropriations bills

- Apportionments (OMB controls): Tracked via OMB's website or OpenOMB.org

- Obligations (Agencies control): Tracked via SF-133 monthly reports

Each step is legally required. Each step is controlled by a different institution. And each step generates different data.

In the Head Start case, tracking all three data points would have revealed the impoundment in real time. The gap between the FY2024 disbursement pace ($2.397B by mid-April) and the FY2025 disbursement pace ($1.572B by mid-April) showed an $825 million withholding. But it took months for GAO to investigate and issue a decision—by which time the damage was done.

This is why real-time tracking matters. If advocates, journalists, and congressional staff can identify delayed apportionments as they happen—not months later when GAO issues a report—they can raise alarms while there's still time to act.

What's Next

Now that we've covered the legal framework, we can dive into the mechanics. We'll talk about the three primary source documents that form the three-legged stool of budget execution - appropriations text, apportionments, and the SF-133 budget execution documents.

Understanding the law isn't enough—you also need to understand the data. But without the legal framework, the data doesn't make sense.

Because budget execution isn't just accounting. It's constitutional law, playing out every day in apportionment and funding decisions that most people never see.

References

Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, Pub. L. No. 93-344, Title X, 88 Stat. 297, 332-39 (July 12, 1974). Codified at 2 U.S.C. §§ 681-688. ↩︎

Congressional Research Service, "Impoundment Control Act of 1974: Overview and Issues" (Updated January 2023), p. 2. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45870 ↩︎

2 U.S.C. § 683. Rescission of budget authority. ↩︎

2 U.S.C. § 684. Proposed deferrals of budget authority. (Note: The legislative veto provision was struck down in INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983), leaving the notification requirement but limiting congressional override power.) ↩︎

2 U.S.C. § 681(a). Presidential authority to effect rescission or to withhold budget authority must be reported to Congress. ↩︎

GAO, "Principles of Federal Appropriations Law" (4th Edition, 2016), Chapter 2, Section D: "Impoundment Control Act." Available at: https://www.gao.gov/legal/appropriations-law/red-book ↩︎

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2025 (enacted December 2024). The Children and Families Services Programs account received $14,789,089,000 for FY2025, including funds for Head Start. See GAO, Department of Health and Human Services—Application of Impoundment Control Act to Availability of Head Start Program Funds, B-337202 (July 23, 2025), p. 3. ↩︎

42 U.S.C. § 9835. Head Start Act: "The Secretary shall allocate funds appropriated under this subchapter... among the States in accordance with" the statutory formula. See also GAO Decision B-337202, pp. 3-4 (describing Head Start as a formula grant program). ↩︎

GAO Decision B-337202, pp. 3-4. National Head Start Association survey (February 4, 2025) found that "at least 45 grant recipients, serving nearly 20,000 children ages zero to five and their families, are experiencing delays in accessing funds. This includes grant recipients in 23 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico." ↩︎

GAO Decision B-337202, p. 1. "Based on this evidence, we conclude that HHS violated the ICA." ↩︎

2 U.S.C. § 686(b)(1). The ICA's "fourth disclaimer" prohibits withholding funds for programs with "a provision of law which requires the obligation of budget authority or the making of outlays thereunder." GAO concluded that the Head Start Act constitutes such a mandate. GAO Decision B-337202, pp. 9-10. ↩︎

BlazingStar Analytics is building real-time budget execution tracking that connects appropriations, apportionments, and SF-133 reports. Get early access to our platform, launching March 2026.