The Three-Legged Stool: Why Federal Budget Tracking Requires Three (or more!) Data Sources

Understanding federal spending requires tracking three distinct processes that most people assume are the same thing.

Understanding federal spending requires tracking three distinct processes that most people assume are the same thing.

When Congress passes an appropriations bill, most people assume the money flows immediately to agencies and programs. It doesn't.

Federal budget execution operates on a "three-legged stool": appropriations, apportionments, and execution. Miss any one of these legs, and you can't see what's actually happening with taxpayer dollars.

Quick Reference: The Three-Legged Stool

To track federal budget execution, you need three data sources:

1. Appropriations (What Congress Provided)

- What it shows: Maximum amount authorized for each program

- Where to find it: Congress.gov (enrolled bills), appropriations bill text

- Key identifier: Appropriations account title

- Key question: How much did Congress appropriate for this account?

2. Apportionments (What OMB Released)

- What it shows: How much funding OMB actually released to agencies (and when)

- Where to find it: OMB website or OpenOMB.org (SF-132 forms)

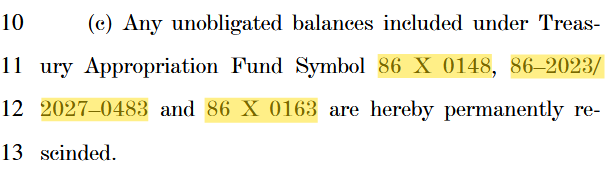

- Key identifier: Treasury Account Fund Symbol (TAFS) like

086-X-0192 - Key question: Has OMB apportioned the full amount Congress appropriated?

3. SF-133 Reports (What Agencies Spent)

- What it shows: Actual obligations and outlays by account

- Where to find it: MAX.gov (monthly Excel files, 15-20 day lag)

- Key identifier: Same TAFS code across all three sources

- Key question: Has the agency obligated the apportioned funds?

Why all three matter:

- Appropriations alone don't show if OMB is withholding funds (impoundment)

- Apportionments don't show if agencies are slow to execute

- SF-133 reports don't explain why spending is delayed

The HUD example below shows how funding for HUD's RUSH program—disaster assistance for people experiencing homelessness—is visible only by comparing all three sources.

The Problem: Appropriation ≠ Availability ≠ Spending

Congress appropriates $3.4 billion for HUD's Homeless Assistance Grants. How much of that money is available to homeless services providers today? How much has actually been spent?

These seem like simple questions. They're not.

Appropriations tell you what Congress authorized. Apportionments tell you what the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) released to HUD. SF-133 reports tell you what HUD actually obligated and spent. These are three different numbers, tracked in three different systems, updated on three different schedules.

The gap between what's appropriated and what's available—or between what's available and what's spent—can reveal impoundments, policy disputes, implementation problems, or simply bureaucratic delays. But tracking these gaps requires connecting data sources that weren't designed to talk to each other.

Leg One: Appropriations (What Congress Provides)

The appropriations process is the most visible leg of the stool. Congress passes 12 appropriations bills each year[^1], specifying how much money each agency can spend and, often, exactly how they can spend it.

These bills are published as enrolled legislation on Congress.gov in both PDF and XML formats. Each appropriation is tied to a Treasury Account Fund Symbol (TAFS)—a unique identifier that follows the money through the entire federal financial system[^2].

A TAFS code looks like this: 086-X-0192

086= Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)X= Multi-year funding (available until expended)0192= Homeless Assistance Grants

This identifier is the key to connecting appropriations to execution. When Congress appropriates money to account 086-X-0192, you can track that same account through OMB apportionments and Treasury execution reports.

Key limitation: Appropriations bills tell you the maximum amount authorized, but they don't tell you when—or whether—that money will actually be released to agencies.

- What is an Appropriation? Understanding Congress's Power of the Purse

- How Appropriations Work: Duration and Distribution

Leg Two: Apportionments (What OMB Releases)

After Congress appropriates funds, agencies can't immediately spend them. First, they must request an apportionment from OMB—essentially asking permission to use the money Congress just gave them[1].

This is where things get complicated.

OMB can (and does) apportion funds on a restricted schedule. Instead of releasing the full annual appropriation at once, OMB might release funds quarterly, monthly, or according to a specific timeline. This gives the White House significant control over the timing and pace of federal spending, even after Congress has appropriated the money[2].

Apportionments are submitted through OMB's MAX system and reviewed (or modified) by OMB budget examiners and approved by an Associate Director. Once approved, agencies receive an SF-132 form that specifies:

- How much of the appropriation is available to obligate

- When those funds are available (by time period)

- Any restrictions on how funds can be used

- Whether funds are apportioned by category, program, or project

The transparency problem: Until 2020, apportionments were only available through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests or by accessing OMB's internal MAX system (which requires agency credentials). Congress changed this in 2020, requiring OMB to publish apportionments within two days of approval[3].

Today, you can find apportionments on OMB's website[4] or on OpenOMB.org, a public portal run by the Protect Democracy Project[5]. But even with this transparency requirement, apportionments remain difficult to use: they're published as individual Excel and JSON files with no bulk download, and no connection to execution data.

Leg Three: SF-133 Reports (What Agencies Actually Spend)

The final leg is execution data: what agencies actually obligate and spend.

Every month, federal agencies submit financial data in the Governmentwide Treasury Account Symbol Adjusted Trial Balance System (GTAS) [6] which OMB releases as SF-133 Report on Budget Execution and Budgetary Resources [7]. These reports show, for each TAFS account:

- Budgetary resources (total funds available)

- Obligations incurred (money committed through contracts, grants, or other legal commitments)

- Outlays (actual cash payments)

- Unobligated balances (money not yet committed)

The SF-133 is the most detailed public view into federal budget execution. Treasury publishes these reports on MAX.gov (the public-facing portal, not the internal OMB system), typically 15-20 days after the end of each month.

Here's the catch: SF-133 reports are published as Excel files with 85+ columns of budget data. The column headers use Treasury accounting terminology like "Line Number 1910" or "Total Budgetary Resources (Line 1000)." Without understanding the SF-133 line item structure, the data is nearly unusable.

Key limitation: SF-133 reports tell you what agencies have spent, but they're a lagging indicator—published weeks after the reporting period ends. And they don't tell you why spending is higher or lower than expected.

Why You Need All Three

Let's walk through a real example using HUD's Homeless Assistance Grants (TAFS 086-X-0192).

Appropriations:

Section 231 of the “Housing and Urban Development Appropriations Act, 2019” allows for recaptured Homeless Assistance Grant funding to be transferred into a no-year account and used for homeless assistance activities in future fiscal years. The law required that not less than 10 percent be reserved for activities in rural areas, and not less than 10 percent be reserved for activities to assist survivors of natural disasters who were experiencing or were at risk of homelessness. [8] HUD created the Rapid Unsheltered Survivor Housing (RUSH) program to provide assistance to survivors of natural disasters using this funding.

Apportionments: "This is the hidden gem: There's no way to know how much funding exists without checking the apportionment. Congress.gov won't tell you. The appropriations bill text won't tell you. USAspending.gov won't tell you (obligations are downstream). The only way to discover that $548 million is available is to check OMB's SF-132 apportionment file." For example, if you are a community that has recently experienced a natural disaster, it can be especially challenging to identify exactly how much funding is accessible for your community's needs.

On September 29, 2025, OMB approved HUD's FY2026 apportionment for Homeless Assistance Grants[9]. The apportionment shows:

- Total available: $548,149,699 (recaptures + prior-year carryover)

- Released for obligation: $69,171,908 (Line 6019, apportioned for Emergency Solutions Grants for Disaster Areas)

- Unallocated: $86,961,191 (available to be distributed to the four activites)

Now you know $69 million is available. But has HUD actually obligated it to homeless services providers?

SF-133: The September 2025 SF-133 report for account 086-X-0192 shows[10]:

- Obligations incurred (cumulative): $128,593,122

- Unobligated balance: $547,433,091

- Obligations to Disaster Areas: $37,152,677

Why this matters for disaster-affected communities:

If you're a city dealing with wildfire recovery or hurricane damage, you need to know:

- Does funding exist? (Apportionment says YES: $69M available)

- Has HUD released it to grantees? (SF-133 says PARTIALLY: $37M obligated, $32M gap)

- Is more coming? (Apportionment shows $87M still unallocated among four activities)

Without tracking all three sources, you're flying blind. You might not even know to apply for the funding.

The Missing Infrastructure

Federal budget transparency advocates often focus on appropriations (lobbying Congress) or outlays (tracking contracts and grants). But the middle leg—apportionments—is where execution actually happens.

And even with the 2020 transparency requirement, it's still largely invisible.

The Congressional Budget Office tracks appropriations. USAspending.gov tracks contracts and grants (downstream from obligations). OMB publishes apportionments as individual Excel files. But there's no system that connects these three data sources, no alerts when funds are released or withheld, no historical analysis of apportionment patterns.

This opacity matters. When OMB withholds apportionments, agencies can't spend money even if Congress appropriated it. This is how impoundments happen—not through dramatic announcements, but through quiet administrative delays[11].

What's Next

In the coming weeks, we'll break down each leg of the stool in detail, but first we'll need to get acquainted with the TAFS — the universal identifier that connects everything.

Budget execution tracking shouldn't require a PhD in federal accounting. Our goal is to make these three data sources—appropriations, apportionments, and SF-133 reports—accessible, connected, and useful.

Because right now, tracking federal spending is like trying to assemble a puzzle when two-thirds of the pieces are hidden in different rooms.

References

Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11: Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, Section 120 (August 2025). "An apportionment is a distribution made by OMB of amounts available for obligation in an appropriation or fund account." Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/a11.pdf?page=363 ↩︎

GAO, "Principles of Federal Appropriations Law" (4th Edition, 2016), Chapter 2: "The Legal Framework." The Antideficiency Act requires OMB apportionment before agencies can obligate funds. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/legal/appropriations-law/red-book ↩︎

Public Law 117-103, "Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022," Division E, Title II, Section 204 (March 15, 2022), 136 Stat. 256. Available at: https://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/117/103.pdf?page=256. This provision requires OMB to publish apportionments and reapportionments within two business days of approval. ↩︎

Office of Management and Budget Approved Apportionments. Available at: https://apportionment-public.max.gov/ ↩︎

OpenOMB.org, Protect Democracy Project. Available at: https://openomb.org/ ↩︎

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury Financial Manual, Volume I, Part 2, Chapter 4700, "Federal Agencies' Centralized Trial Balance System (GTAS)" (Effective October 2023). Available at: https://tfx.treasury.gov/tfm/volume1/part2/chapter-4700-federal-entity-reporting-requirements-financial-report-united-states The SF-133 is the monthly GTAS submission. ↩︎

MAX Information and Reports (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Users) : SF 133 Report on Budget Execution and Budgetary Resources. Available at: https://portal.max.gov/portal/document/SF133/Budget/FACTS II - SF 133 Report on Budget Execution and Budgetary Resources.html ↩︎

Public Law 116-94, "Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020", Division L, Title II, Sec. 231 (December 20, 2019), 133 Stat. 3008. Codified at 42 U.S.C. § 11364a. Available at: https://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/116/94.pdf?page=476. ↩︎

Office of Management and Budget, Apportionment for Department of Housing and Urban Development, Account 086-X-0192 (Homeless Assistance Grants), Fiscal Year 2026, approved September 29, 2025. Available at: https://apportionment-public.max.gov/Fiscal Year 2026/Department of Housing and Urban Development/Excel/FY2026_Agency%3DHUD_Bureau%3DCOMP%26D_Account%3D086-01922025-09-29-18.44.xlsx ↩︎

Office of Management and Budget, SF-133 Report on Budget Execution and Budgetary Resources for Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 2025. Available at: https://portal.max.gov/portal/document/SF133/Budget/attachments/2580777874/FY2025_SF133_MONTHLY_Department_of_Housing_and_Urban_Development.xlsx ↩︎

Congressional Research Service, "Impoundment Control Act of 1974: Overview and Issues" (Updated January 2023). Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45870 ↩︎

BlazingStar Analytics is building real-time budget execution tracking that connects appropriations, apportionments, and SF-133 reports. Get early access to our platform, launching March 2026.